Sorry, copyright restrictions prevent us from showing this object here

In Tate Liverpool

Ideas Depot

Free- Artist

- Nelson Stevens born 1938

- Medium

- Screenprint on paper

- Dimensions

- Frame: 1122 × 894 × 40 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the Ford Foundation 2018

- Reference

- P82570

Summary

Uhuru 1971 is a screenprint on paper produced by Nelson Stevens, a member of the Chicago-based artists’ collective AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists). Uhuru takes its title from the Swahili word for freedom. Adopted as a fundamental principle of the Pan-African movement, Stevens centres on the hopeful spiritualism associated with the word. Here it is emblazoned above a portrait of an African American woman who gazes upwards with a strong expression. Her face and Afro hairstyle are made up of fragmented and frenzied lines and forms, typical of Stevens’s painting aesthetic, evoking rhythm and movement inspired by African music.

Founded in 1968 and still active, the AfriCOBRA collective defined its mission as ‘an approach to image making which would reflect and project the moods, attitudes, and sensibilities of African Americans independent of the technical and aesthetic strictures of Euro-centric modalities.’ (Quoted at https://arts.uchicago.edu/logan-center/logan-center-exhibitions/archive/africobra-philosophy, accessed November 2017.) Its members produced works individually, but based on a common aesthetic language, in the effort to produce a new African American socio-political art movement in response to the growing Black Power movement in the United States. The collective was formed at a meeting held by Jeff Donaldson with fellow founding members, Jae Jarrell, Wadsworth Jarrell, Barbara Jones-Hogu and Gerald Williams to discuss the visual tropes that would innately reflect Black identity and a philosophy that would underpin a new Black art movement. A number of the artists linked with AfriCOBRA were also members of OBAC (Organisation of Black American Culture) that produced the Wall of Respect 1967–71, a historically significant mural on the south side of Chicago that celebrated key figures within Black culture and society. Speaking of the formation of AfriCOBRA, Jones-Hogu has recounted: ‘We had all noted that our work had a message: it was not fantasy or art for art’s sake; it was specific and functional because it expressed statements about our existence as Blacks.’ (Jones-Hogu 2012, p.92.) Joined later by artists Nelson Stevens and Carolyn Lawrence among others, the group produced work according to a series of aesthetic principles, collaboratively established and formally outlined by Donaldson in a manifesto, ‘Ten in Search of a Nation’, published in Black World in 1970, soon after the collective held its first exhibition, in the summer of 1970 at the Studio Museum Harlem in New York.

The new aesthetic was based on ‘rhythm’, ‘shine… the rich lustre of a just-washed ’Fro …’ and ‘Colour colour Colour colour that shines, colour that is free of rules and regulations’ (Donaldson 1970, p.82). Text would often be incorporated into the pictures, anchoring messages that focused on themes ranging from the Black family to Black Nationalism, taking inspiration from the rhythm and movement of African music and using everyday source material, such as the colours of the Kool-Aid branding of cola flavours. Donaldson articulated the inclusive nature of the group’s outlook, stating: ‘We strive for images inspired by African people – experience and images that African people can relate to directly without formal art training and/or experience. Art for people and not for critics whose peopleness is questionable. We try to create images that appeal to the senses – not to the intellect.’ (Ibid., p.81.)

Stevens’s Uhuru is one of a group of silkscreen prints in Tate’s collection produced collaboratively as a way of making affordable renditions of the most popular paintings from the AfriCOBRA exhibition at the Studio Museum in 1970. (See also Jeff Donaldson [1932–2004], Victory in the Valley of Eshu 1971, Tate P82525; Barbara Jones-Hogu [1938–2017], Unite 1971, Tate P82569; Gerald Williams [born 1941], Wake Up 1971, Tate P82571; Carolyn Lawrence [born 1940], Uphold Your Men 1971, Tate P82572; and Wadsworth Jarrell [born 1929], Revolutionary 1972, Tate P82573.) The original painting by Stevens that the Uhuru print is based was not shown in the exhibition at the Studio Museum, but the image was selected by the artist for his contribution to the collective’s print project. Termed ‘poster-prints’ by the collective, they were sold to the public for ten to fifteen dollars each at exhibitions and local street art fairs. The production of the prints began in the summer of 1971 under the guidance of Jones-Hogu in her printmaking studio in Chicago. Donaldson’s Victory in the Vallery of Eshu was printed a year later in Washington D.C. and is based on a mixed media painted collage produced after the 1970 exhibition. Wadsworth Jarrell’s Revolutionary was printed in 1972, and sold and distributed in the same way as the other prints. The editions were often not signed by the individual artists in order to prioritise the collective effort of the group over individual identity. However, some copies were later signed, as is the case with Tate’s versions which are from the original set of impressions and remained in the artists’ possession.

Further reading

Jeff Donaldson, ‘Ten in Search of a Nation’, Black World, October 1970, pp.80–6.

Barbara Jones-Hogu, ‘Inaugurating AfriCOBRA: History, Philosophy and Aesthetics’, NKA: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Spring 2012, pp. 90–7.

Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley (eds.), Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2017, pp.88–97.

Priyesh Mistry

November 2017

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

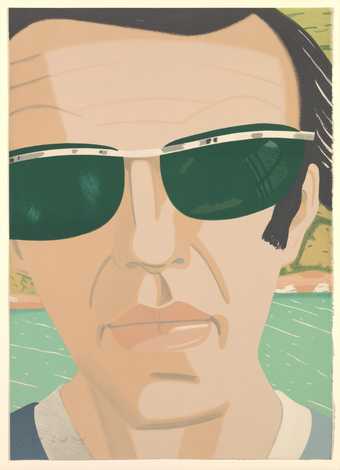

Alex Katz Alex

1970 -

Roy Lichtenstein Untitled (Paper Plate)

1969 -

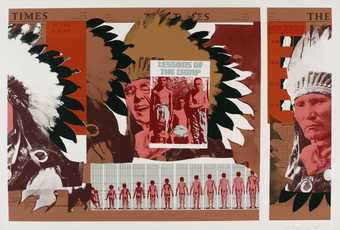

Ronald Stein Lessons of the Camp

1967 -

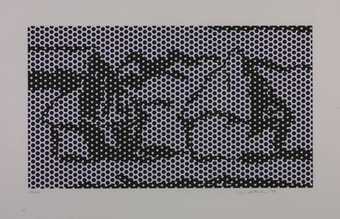

Roy Lichtenstein Haystacks #3

1969 -

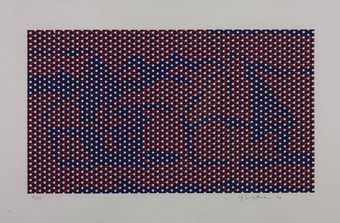

Roy Lichtenstein Haystacks #4

1969 -

Roy Lichtenstein Haystacks #5

1969 -

Roy Lichtenstein Haystacks #6

1969 -

Robert Cottingham Carl’s

1977 -

Robert Cottingham Black Girl

1980 -

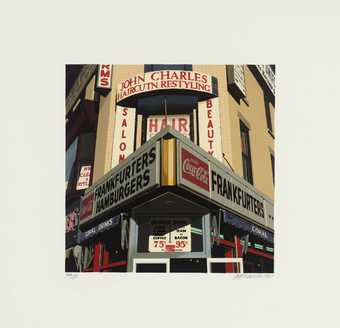

Robert Cottingham Frankfurters

1980 -

Robert Longo Jules, Gretchen, Mark, State II

1982–3 -

Roy Lichtenstein Still Life with Portrait from ‘Six Still Lifes’

1974 -

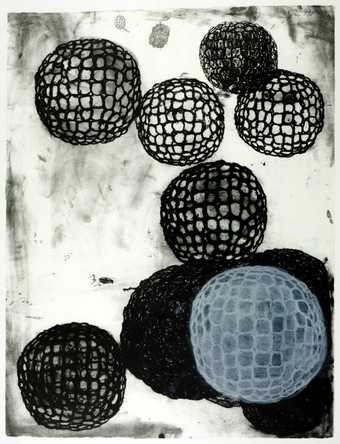

Terry Winters Morula II

1983–4 -

Terry Winters Morula III

1983–4 -

Ad Reinhardt [no title]

1964