On loan

Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (Tokyo, Japan): David Hockney, in collaboration with the Hockney Studio

- Artist

- David Hockney born 1937

- Medium

- Inkjet prints on paper, mounted on aluminium; assisted by jonathan wilkinson

- Dimensions

- Displayed: 2781 × 7601 × 25 mm

support, each: 2781 × 1086 mm (7 in total) - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the artist 2018

- Reference

- T15144

Summary

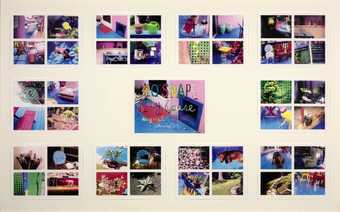

In the Studio, December 2017 2017 is a panoramic colour photographic image of David Hockney standing in his studio in the Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles. The back and side walls are fully hung with paintings made over the previous nine months and a number of paintings and drawings lean against the base of both walls. At the right edge two easels hold paintings and, standing proud of the left wall, another easel holds a third painting. Hockney stands to the left of a large Persian rug, off-centre and facing straight out; he wears a striped cardigan. Around him are positioned two stools and two armchairs, as well as a copy of his SUMO retrospective book, published by Taschen in 2016, which is shown open on a book stand. The viewpoint is from high up, looking down into the studio yet the image’s structure does not conform to conventional photographic one-point perspective, but rather to a moving focus around each object in the studio.

In the Studio, December 2017 is the sum of manipulating over 3,000 photographs of the studio set-up that had been stitched together digitally to produce what Hockney described in 2014 as a ‘photographic drawing’ (David Hockney, 2017, p.193). The first works he made of this type were crude compared to the images of the studio he created in 2017 and 2018; these were the result of using Agisoft PhotoScan photogrammetric software that would combine the hundreds of details of an image and individual objects to create what Hockney described as a ‘three dimensional approximation through which a toggle-wielding viewer could then manoeuvre, rising through, descending, tilting, and rebalancing the surround, focusing this way and that, in and out, up and down’ (quoted in Pace 2018, pp.18–19). Hockney has described how he and his assistant Jonathan Wilkinson used the 3D software to make ‘360-degree tours of various individual objects – a stool, an easel, a chair, a rug, the Taschen SUMO book on its dedicated tripod stand … and then waited as their laptop … generated notional digital objects that could be moved about the notional space.’ (Quoted in Pace 2018, pp.18–19.)

The sense of a three-dimensional moving focus that Hockney achieved with this and related works connected with his much earlier experimentation with photographic collages or ‘joiners’ in the 1980s that culminated with Pearblossom Hwy., 11–18th April 1986 1986 (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) – an image of a desert highway crossing made up of a collage of over 800 individual photographs. The experimentation that Hockney carried out in the 1980s into a use of photography that undermined its technical restriction to one point perspective in favour of images that shifted their focal point also reflected and confirmed changes that were taking place in his painting by 1980 – away from the naturalism of the ‘Double Portraits’ of the early 1970s (such as Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy 1970–1 [Tate T01269]) in favour of paintings that involved a mobile rather than static viewer, first indicated by the painting Mulholland Drive, The Road to the Studio 1980 (Los Angeles County Museum). Such paintings reflected his growing certainty that painting had to be as close to actual lived experience as possible and, if the viewer or artist is mobile, then the resulting painting should be infused with multiple perspectives and moving focus.

Another aspect of Hockney’s renewed thinking about picture-making in the 1980s had revolved around reverse perspective – a way of picturing that effectively reversed perspectival vanishing points. Since returning to Los Angeles in 2013, Hockney engrossed himself with picturing movement in the studio as a means of explicitly concentrating on ways of realising a moving focus in his work – harnessing both paint and digital technology – according to his principle that ‘the eye is always moving; if it isn’t moving you are dead. When my eye moves the perspective alters according to the way I’m looking, so it’s constantly changing; in real life when you are looking at five people there are a thousand perspectives.’ (Quoted in Martin Gayford, ‘Hockney’, in Pace 2014, p.8.)

In the spring of 2014 he started to paint groups of figures standing and sitting in the studio looking at some of the finished portraits hanging there. Figures might be repeated in the same picture, looking both at a wall of pictures and out towards the viewer of the painting, or they might be positioned in the studio to emphasise the moving focus of Hockney’s eyes. These, and the paintings that followed using dancers, are concerned primarily with pictorial space, and how groups of people move and position themselves within that space. For Hockney these paintings, making a direct reference to Henri Matisse’s (1869–1954) painting Dance 1911, confirmed how ‘the still picture can have movement because the eye moves’ (quoted in Pace 2014, p.11). This then led him to make the first of his photographic drawings, again set in the studio with representations of recent and old work acting as visual prompts for the viewer.

In the Studio, December 2017 captures the developments made immediately after the opening of Hockney’s solo exhibition at Tate Britain, London in 2017 – again, bringing together paint and digital technology. The photographic drawing gathers together the different paintings he made, constructed using reverse perspective that led him to create shaped canvases to emphasise this principle. The subject of the paintings also significantly alters; from the terrace of his home (Interior with Blue Terrace and Garden 2017, created using a conventional landscape format canvas, and A Bigger Interior with Blue Terrace and Garden 2017, the fourth of his paintings to use a shaped canvas); to invented compositions that play between interior and exterior and the positioning of different objects – stones, chairs, flowers and versions of other artist’s works (Fra Angelico’s Annunciation 1437–46 or Meindert Hobbema’s The Avenue at Middelharnis 1689 [National Gallery, London]); before also tackling his own work. Still Life 2017 recalls a motif from Hockney’s Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices 1965 (Arts Council Collection, London); Garrowby Hill 2017 recalls the painting of the same title of 1998 that is also reproduced in the photographic drawing – being the spread displayed from the Taschen book. He also revisited his use of the Grand Canyon, Nichols Canyon and the Hotel Acatlan as prior subjects that had already been suggestive of the presence of reverse perspective.

As well as being a portrayal of a large body of work before it leaves the studio for exhibition, In the Studio, December 2017 continues a polemical purpose within Hockney’s art, making clear the shifts in his subject-matter as he moved beyond naturalism by the end of the 1970s – to make work that encompasses how we see and respond to the world around us. The studio is both a place of artistic creation and self-referential subject. It is more specifically the location where Hockney’s consistent questioning and hard looking results in pictures – depictions and representations – that could equate with how we experience the world. Hockney’s ambition and use of the studio as motif in this way directly connects with significant art historical precursors such as Henri Matisse’s The Red Studio 1911 (Museum of Modern Art, New York) and Gustave Courbet’s (1819–1877) The Painter’s Studio – A real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life 1855 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris).

Further reading

David Hockney, Some New Painting (and Photography), exhibition catalogue, Pace, New York 2014.

David Hockney, Painting and Photography, exhibition catalogue, Annely Juda Gallery, London 2015.

Chris Stephens, Andrew Wilson (eds.), David Hockney, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2017.

David Hockney, Something New in Painting (and Photography) [and even Printing], exhibition catalogue, Pace, New York 2018.

Andrew Wilson

August 2018

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

David Hockney Two Pembroke Studio Chairs

1984 -

David Hockney Pembroke Studio Interior

1984 -

David Hockney Pembroke Studio with Blue Chairs and Lamp

1984 -

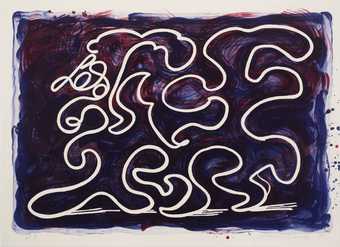

David Hockney White Lines Dancing in Printing Ink

1990 -

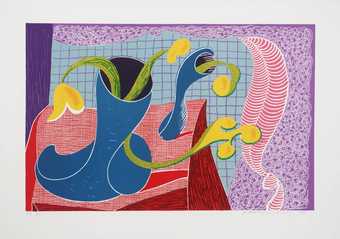

David Hockney Four Flowers in Still Life

1990 -

David Hockney The Wave, A Lithograph

1990 -

David Hockney Très (End of Triple)

1990 -

David Hockney Eine (Part I)

1991 -

David Hockney Table Flowable

1991 -

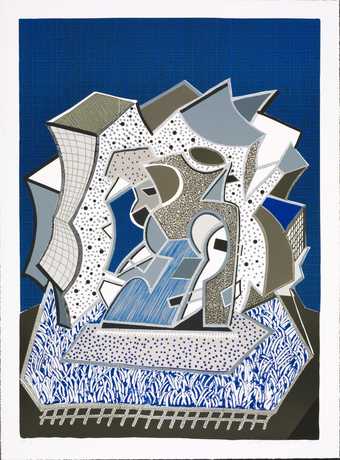

David Hockney The New and the Old and the New

1991 -

David Hockney Rampant

1991 -

David Hockney Deux (Second Part)

1991 -

David Hockney Twelve Fifteen

1991 -

David Hockney 40 Snaps of my House, August 1990

1990