In Tate Britain

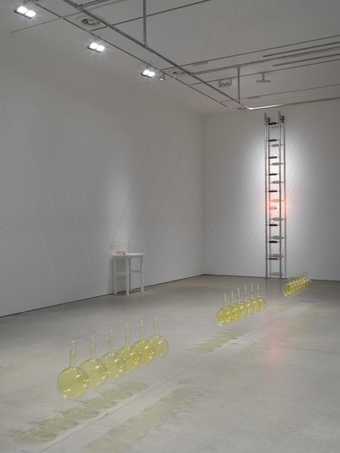

- Artist

- Hamad Butt 1962–1994

- Medium

- Glass, steel, ultraviolet lights and electrical cables

- Dimensions

- Overall display dimensions variable

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by Jamal Butt 2019

- Reference

- T15512

Summary

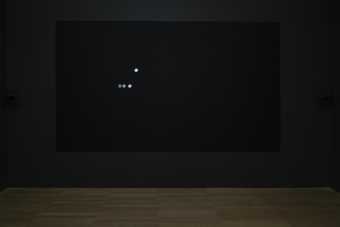

Transmission 1990 is an installation consisting of nine glass books resting on metal stands, each individually lit by its own ultraviolet light. The books are arranged in a circle on the floor, connected by electrical cabling, each of their nine glass pages turned in progressively ascending order. On the same page of each book the image of a single Triffid from the cover of John Wyndham’s novel The Day of the Triffids (1951), a creature bulbous at one end but with an agile, probing snout at the other, is etched into the glass. The effect created is an image of the Triffid that, although always discernible upon close inspection, moves in and out of visibility as the viewer moves around the circle. The single Triffid seems to rise to the surface of the page, taking on an almost phallic symbolism. Butt was fascinated by the image of the Triffid from Wyndham’s novel and the relationship this iconic book had with the unease of the social body. In the novel the Triffids pray upon an unsuspecting populous, blinded by an apparent meteor shower. Describing the Triffid, Butt wrote, ‘On the cover of the book, an image of a creature that is not anything as distant as the castrated male genitalia, yet it creeps to that dreaded desire as it takes the power of mobilisation itself.’ (Hamad Butt, ‘Apprehensions’, in Foster 1996, p.50.) In one of his working notebooks, part of Butt’s archive held at Tate, he wrote that, ‘The Triffid exists in exile. The alienated exile of the dangerous, ejaculating, contaminated pudenda,’ reflecting a personal exile and alienation felt by Butt himself.

When the work was first displayed in the 1990 student exhibition at Goldsmith’s School of Art, London, and for its subsequent presentation later that year at Milch Gallery, London (the only exhibitions of the work in Butt’s lifetime), the artist invited visitors to enter the circle of books and sit down in the centre. They were instructed to put on a pair of protective googles and approach each of the glass books in turn to decipher the image etched into the glass pages.

In these two exhibitions of Transmission Butt also included nine statements, as follows:

We have the ‘Black light’ that is Ultra-Violet.

A penetrative radiation that damages human sight.

A seductive invisibility that fascinates flies.

We have the eruption of the Triffid that obscures sex with death

A stigmata of an era with the fear of invasions

A mark of contagion that isolates others, defiles intimacy

We have the blindness of fear and the books of fear.

We have the dangers of blind faith (prayer) and the transmissions of faithlessness (distraction)

We have the apprehensions that regard these words before strategic withdrawal

In the first exhibition a glass vitrine was mounted on the wall of the gallery, containing sugar paper inscribed with the nine phrases. Inside were maggots placed at the bottom of the vitrine that would eventually hatch into flies, feeding on the sugar paper until they died. In the second exhibition the statements were sandblasted onto the glass of the Milch Gallery windows. At both there was also a monitor that displayed the same image of the Triffid.

In a notebook of Butt’s from the time when he made Transmission, he broke the work down into six key elements: the Triffid, representing ‘historical periods of fear’; the ‘pervasive and invisible visible’ ultraviolet lights; the ‘transparent, sharp, penetrative’ glass of the books; the telephone cables that transmit electricity; the flies as the site of ‘decay and transmission’; and the book supports.

In his essay ‘Apprehensions’, written to accompany the exhibition of Transmission at Goldsmith’s, Butt wrote, ‘The triffids blind their victims, the comet blinds the populace, light in excess blinds the viewer’ (in Foster 1996, p.50). If viewers were to attempt to discern the etched motif without wearing the protective glasses, the ultraviolet light would damage their eyes, drawing attention to what Butt saw as the violence caused by scientific knowledge in establishing its pre-eminence. Quoting the philosopher Paul Virilio, Butt stated, ‘Thus in this mediated or information society we are isolated in a state of pure seeing … we are seeing without knowing.’ (In Foster 1996, p.43.) Butt was preoccupied with the privilege of vision, in particular the diagnostic gaze in the understanding and cataloguing of human disease. He understood that a body treated as an object can no longer defend itself but, by engaging with the physiognomy of ‘fear’ in one’s experience of Transmission, Butt wanted to offer a way out. In this process fear could symbolically overcome death and, by ritualising the threat of death, he attempted to somewhat stabilise the disturbances of experience.

Throughout Butt’s writings and art, a narrative of increasing vulnerability and worry concerning the invasion of the body by an alien substance (deadly chemicals) or disease (AIDS) occurs; a vulnerability that is captured in the title of this work. ‘Transmission’ suggests a blind or hidden exchange between entities that may be out of our control. Transmission is the site of Butt’s earliest exploration of the nexus between science and art, reason and danger and, ultimately, life and death; the ideas he would go on to explore and materialise in the related installation Familiars 1992 (Tate T14779), also in Tate’s collection, which would become his final work.

Even though Butt held a deep respect for reason, he resolutely interrogated the power of the intellect. In Transmission, the combination of mystery and popular culture and the suggestion that his malign, yet slightly comical Triffid character might overthrow established institutions of learning was earnest. This was an artist calling for nothing less than a revision of the conventional view of scientific knowledge, replacing it with what he called ‘a critique of the institution of science as, somehow, especially truthful’ and a shift to what he described as ‘a speculative science practice’ (quoted in Alien Nation, exhibition catalogue, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 2006, p.103). Transmission reveals in Butt an idiosyncratic interest in the supernatural, juxtaposed with what he called ‘pure science’, based on empirical research and precise scientific calculation. These seemingly oppositional interests in fact reflect Butt’s training as a biochemist before entering art college.

Further reading

Clement Page, ‘Hamad Butt: The Art of Metachemics’, Third Text, vol.9, no.32, 1995, pp.33–42.

Rites of Passage: Art for the End of the Century, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1995.

Stephen C. Foster (ed.), Hamad Butt: Familiars, London 1996.

Nathan Ladd

March 2019

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

Sir Anthony Caro Quartet

1971 -

Sir Anthony Caro Emma Dipper

1977 -

Sir Anthony Caro Déjeuner sur l’herbe II

1989 -

Tracey Emin Is Anal Sex Legal

1998 -

Rebecca Warren OBE Versailles

2006 -

Rasheed Araeen Lovers

1968 -

David Musgrave Transparent Stick Figure

2009 -

Zahoor ul Akhlaq Untitled

1992–3 -

Zahoor ul Akhlaq Untitled

1992–3 -

Zahoor ul Akhlaq Untitled

1992–3 -

Zahoor ul Akhlaq Untitled

1992–3 -

Hamad Butt Familiars

1992 -

Huma Bhabha Man of No Importance

2006 -

Salman Toor 9PM, the News

2015 -

Lala Rukh Rupak

2016