Not on display

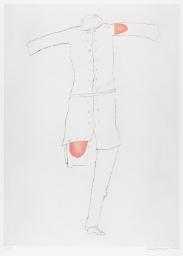

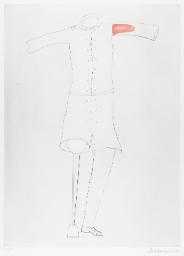

- Artist

- Louise Bourgeois 1911–2010

- Part of

- Autobiographical Series

- Medium

- Drypoint on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 217 × 132 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1994

- Reference

- P77683

Summary

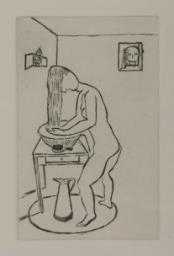

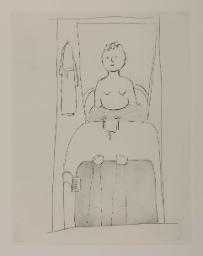

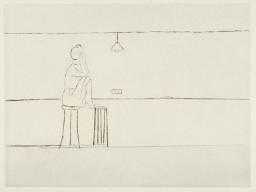

Sewing is one in a portfolio of fourteen drypoint etchings collectively titled Autobiographical Series. It depicts the artist employed in dress-making, a traditionally feminine domestic activity. The dress on the hanger is of a style from the 1960s, referring to an activity remembered from her past. It is not clear what the figure behind the sewing machine is making, perhaps something much larger than a garment. Bourgeois grew up in a family of tapestry restorers in France. In her work, the activity of sewing and the tools it requires (such as needles and scissors) have important symbolic references connected to emotional repair and restoration.

Bourgeois's work is based, more or less overtly, on memory. The recounting of her early years has become a fundamental part of her artistic expression, a narrative which, despite having been told many times, retains for the artist its emotional intensity. Through making art she is able to access and analyse hidden (but uncomfortable) feelings, resulting in cathartic release from them. She has said:

Some of us are so obsessed with the past that we die of it. It is the attitude of the poet who never finds the lost heaven and it is really the situation of artists who work for a reason that nobody can quite grasp. They might want to reconstruct something of the past to exorcise it. It is that the past for certain people has such a hold and such a beauty ... Everything I do was inspired by my early life.

(Bourgeois, p.133.)

Printmaking, like drawing, has been an important element in Bourgeois's artistic production. She first took it up in 1938, the year she moved to New York with her husband, the American art historian Robert Goldwater (1907-73). She experimented widely with techniques and effects, producing an important portfolio of etchings titled He Disappeared into Complete Silence (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) in the 1940s. After a long break she took up printmaking again in 1973, the year her husband died. In the late 1980s Bourgeois began collaborating with workshops and publishers. She started to rework and reprint some of her old plates and to create new portfolios. Several of the images in the Autobiographical Series had already appeared in earlier forms. They range broadly in time and concept, encompassing both specific memories and more abstracted and ambiguous states of being. The portfolio was published in an edition of thirty-five plus ten artist's proofs by Peter Blum Edition, New York, and printed by Harlan & Weaver Intaglio, New York. See Tate P77682 and P77684-95 for the other images in the series.

Further reading:

Louise Bourgeois, Marie-Louise Bernadac, Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Destruction of the Father/Reconstruction of the Father: Writings and Interviews 1923-1997, London 1998

Charlotta Kotick, Terrie Sultan, Christian Leigh, Louise Bourgeois: The Locus of Memory, Works 1982-1993, The Brooklyn Museum, New York 1994

Deborah Wye, Carol Smith, The Prints of Louise Bourgeois, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1994

Elizabeth Manchester

July 2001

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

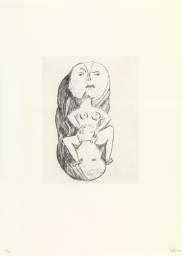

Display caption

Much of Bourgeois' work is autobiographical, and relates to her traumatic childhood. She idolised her mother, and loathed her overbearing, adulterous father. Bourgeois made her first prints in the 1940s and, after a gap of about forty years, returned to printmaking in 1990. Frequently child-like in style, these works portray the events and fantasies of her childhood and adolescence. The scenes include the trauma of birth, the pubescent discovery of the body, the moulding of a daughter by her mother, and the stifling of a daughter by her father.

Gallery label, August 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- memory(367)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- dress(381)

- coat hanger(8)

- sewing machine(10)

- self-portraits(888)

- birth to death(1,472)

-

- childhood(42)

- arts and entertainment(7,210)

-

- artist, sculptor(1,668)

- sewing(28)

You might like

-

Louise Bourgeois Untitled (Safety Pins)

1991 -

Louise Bourgeois Toilette

1994 -

Louise Bourgeois Birth

1994 -

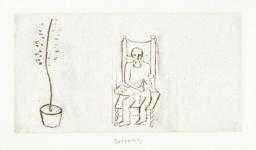

Louise Bourgeois Paternity

1994 -

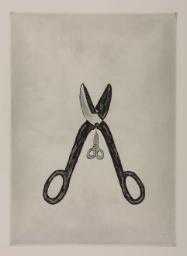

Louise Bourgeois Scissors

1994 -

Louise Bourgeois Woman and Clock

1994 -

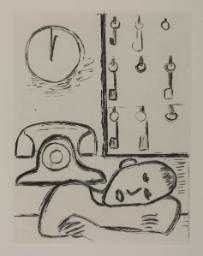

Louise Bourgeois Man, Keys, Phone, Clock

1994 -

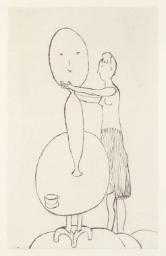

Louise Bourgeois Sculptress

1994 -

Louise Bourgeois Woman in Bathtub

1994 -

Louise Bourgeois Empty Nest

1994 -

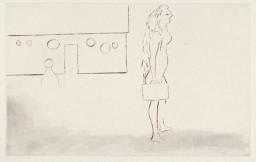

Louise Bourgeois Woman with Suitcase

1994 -

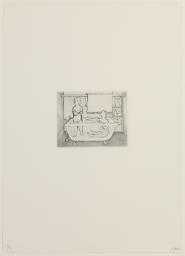

Louise Bourgeois Children in Tub

1994 -

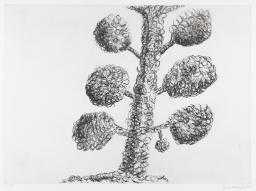

Louise Bourgeois Tree

1998 -

Louise Bourgeois Amputee

1998 -

Louise Bourgeois Amputee with Peg Leg

1998